Breathing is a funny thing. We do it all day long out of necessity and rarely give it much thought. However, just because we do it so often doesn’t necessarily mean we are good at it nor are we getting better at it. In fact, I find that a lot of people suffer from “bad breath.” Their breathing patterns are less than stellar. So what? You may ask.

The thing about our breath is that it is linked to our central nervous system; it is tied to physical performance; it is tied our movements; and it is tied to our pain. We can utilize the breath to up-regulate our nervous system or down-regulate our nervous system. We can move in ways that help or hinder our breath. We can use our breath to help alleviate our pain or to mask it.

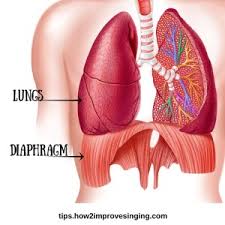

Our main respiratory muscle is the diaphragm. The diaphragm is a key player not only in breath but also in spinal stabilization as it is used to create intra-abdominal pressure. When I assess clients that have chronic pain and/or movement dysfunction they often have “bad breath,” i.e. poor breathing mechanics and poor control of their diaphragm. By teaching people how to breathe properly, I can get them to down regulate and create a physiological state where healing can occur. Proper breathing allows me to better help them stabilize and protect their spines which leads to better, pain-free movement and helps me teach them better movement patterns.

For example, you twist your ankle and it hurts to walk on. Maybe you tore a ligament or strained muscle, you don’t know. All you know is that it hurts. Maybe you went to the doctor, maybe you didn’t. Maybe you took pain killers. It doesn’t matter. Your body senses pain in your foot. Every time you try to walk on it, you wince a little and your body braces itself. It stiffens. You hold your breath a little with each step. You compensate by placing more weight on the other leg and your hips shift with every step. That means your lower back is supported more on one side than the other. After a few days of this, you don’t even know you are compensating and your brain starts to filter out the noise coming from that achy ankle because now you can pretty much get through your day. Six months later your lower back is hurting all the time. You think it’s unrelated. Turns out it is from all the compensating you’ve done to avoid stress on your bad ankle that hasn’t healed.

So are you saying that learning to breathe better will fix my lower back? Not exactly. If you learn to breathe better, you can start to relax a little. That’s important because when you are stress breathing you are up-regulating your sympathetic nervous system (“fight or flight”) and releasing stress hormones. When you learn how to do abdominal-thoracic breathing you down-regulate and activate your parasympathetic nervous system (“rest and digest”) and get back to homeostasis and this allows your body to better heal itself. Furthermore, once we get you to breathe deeply we can then create some intra-abdominal pressure and teach you how to stabilize your spine. Often that helps relieve some of the back pain. Once your spine is stabilized when you stand you won’t shift your weight over and you will put weight on both feet then suddenly you will realize your ankle still hurts. Finally you can start doing something about that ankle.

This all seems convoluted. It is. The body is a complex system of systems. That is why many people suffer injuries over and over or constantly find themselves getting stalled in their progress. The pain isn’t where the problem started. The pain is where the problem stopped. Going back to the start of the pain is the hard part. Breathing is just one of the vehicles that help us on that journey.

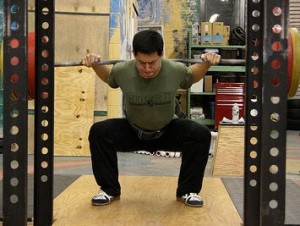

From a practical and functional standpoint, you need to breathe deeper so you can perform better. Learning how to take longer, deeper breaths and create and utilize the full capacity of the lungs is essential to performance. Strengthening the diaphragm is also important because that is one of the stabilizers of the spine. If your spine isn’t stable, you are going to have big problems.

Three Abodes of Breath from Force Distance Time on Vimeo.

The Three Abodes of Breath

As I eluded to before, there are several ways to breathe. The body being intelligent has redundancies built in so that we can always find a way to breathe. See the video above. The first abode is abdominal breathing. In abdominal breathing we utilize the diaphragm to draw air into the lungs. When the central tendon of the diaphragm contracts, it pulls the giant umbrella shaped muscle down and creates a low pressure system in the lungs. The lungs then draw air in air to balance the pressure. Lie comfortably on your back with your knees bent and feet close to your butt. Place one hand on the belly and one hand on the chest. Inhale into the belly and it should rise up under your hand. Exhale and the belly should fall.

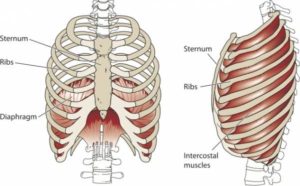

The second abode is thoracic breathing. Thoracic breathing utilizes the intercostal muscles between the ribs to expand the rib cage. The increased diameter of the rib cage creates low pressure in the thoracic cavity and draws air in. Inhale into your chest. The chest should rise up into your hand. You might also feel the back of your ribs press into the floor. ‘

The third abode is clavicular breathing. Clavicular breathing utilizes the levator scapulae and the trapezius muscles to draw the shoulders upward and create low pressure in the upper thoracic cavity and draw air in. Clavicular breathing is associated with stress breathing and panting. It tends to be very shallow. Breath into your shoulders. The shoulders with rise up into your ears. This is called clavicular breathing and should be used infrequently as it is often associated with panic breathing. Unfortunately, many people chronically practice clavicular breathing and are stressed out. Furthermore, they often suffer a lot of shoulder problems because of the overused trapezius muscles that should be doing other things besides helping you breathe all day.

Abdominal Thoracic Breathing

Practice isolating each abode of breath. Compare the sensations associated with each abode. Which one allows you to breathe deepest and which one stresses you out. Now practice abdominal-thoracic breathing. Lie on your back with your eyes closed. Bend your knees and place your heels close to your butt. Place one hand on the belly and one hand on the chest. As you inhale you should feel the belly rise up into your hand first and then the chest rise up into the other hand. On the exhale the chest descends then the belly. Continue breathing like this for 10 cycles. Go as slow as you can comfortably.

You should feel calm and relaxed afterwards. If you find it difficult to breathe like this, you need more practice. Most people try too hard at first which actually makes it more difficult to breathe. Do less. Abdominal-thoracic breathing should be your normal relaxed breathing pattern. Chronic pain and movement dysfunction correlate highly with the inability to perform abdominal-thoracic breathing. Practice breathing this way whenever you become conscious of your breath.

Bridge Lifts

In the next exercise we put it all together and link our movement with our breath. It’s called a bridge lift (I demo these at the end of the video). We start in ardha sivasana lying on our backs with our feet by our butt. Our arms by our side. From here we inhale and lift our hips and arms up. Our hips terminate at the top of a bridge pose and our arms continue until they come to rest by our ears. On the exhale we return our hips to the floor and our arms by our sides. The goal is to synchronize the breathing with the movement. Remember the hips move much slower because they travel a much shorter distance than the arms which travel in a 180-degree arc. This is called a vini or vinyasa. The promise of vinyasa yoga is that evenly metered breath coupled with evenly metered movement will result in an even mind.

You will find that you breathe deeper in the bridge lifts because the movement helps facilitate deeper breaths. One reason is that now you are adding clavicular breathing in addition to the abdominal-thoracic breathing. As the arms rise shoulders get pulled up and help draw in more air. This is proper and normal clavicular breathing that occurs

Practice abdominal thoracic breathing and the bridge lifts and work up to sets of 10 breaths. You should feel relaxed and calm afterward. The goal is to move slower and breathe deeper. Not to go fast and get your heart rate up. Do not take your breathing for granted. There is much to be gained by mastering your breath. Some people say “Master your breath, master your life.” I say, “Breathe fucking harder!”